UGA alumni on the Iditarod Trail

Sonny King (DVM 1978) segued from Iditarod veterinarian to musher. Al Townshend (DVM 1969) turned nutrition knowledge gained on the trail into a 30-year career consulting with pet food companies.

By Amy H. Carter

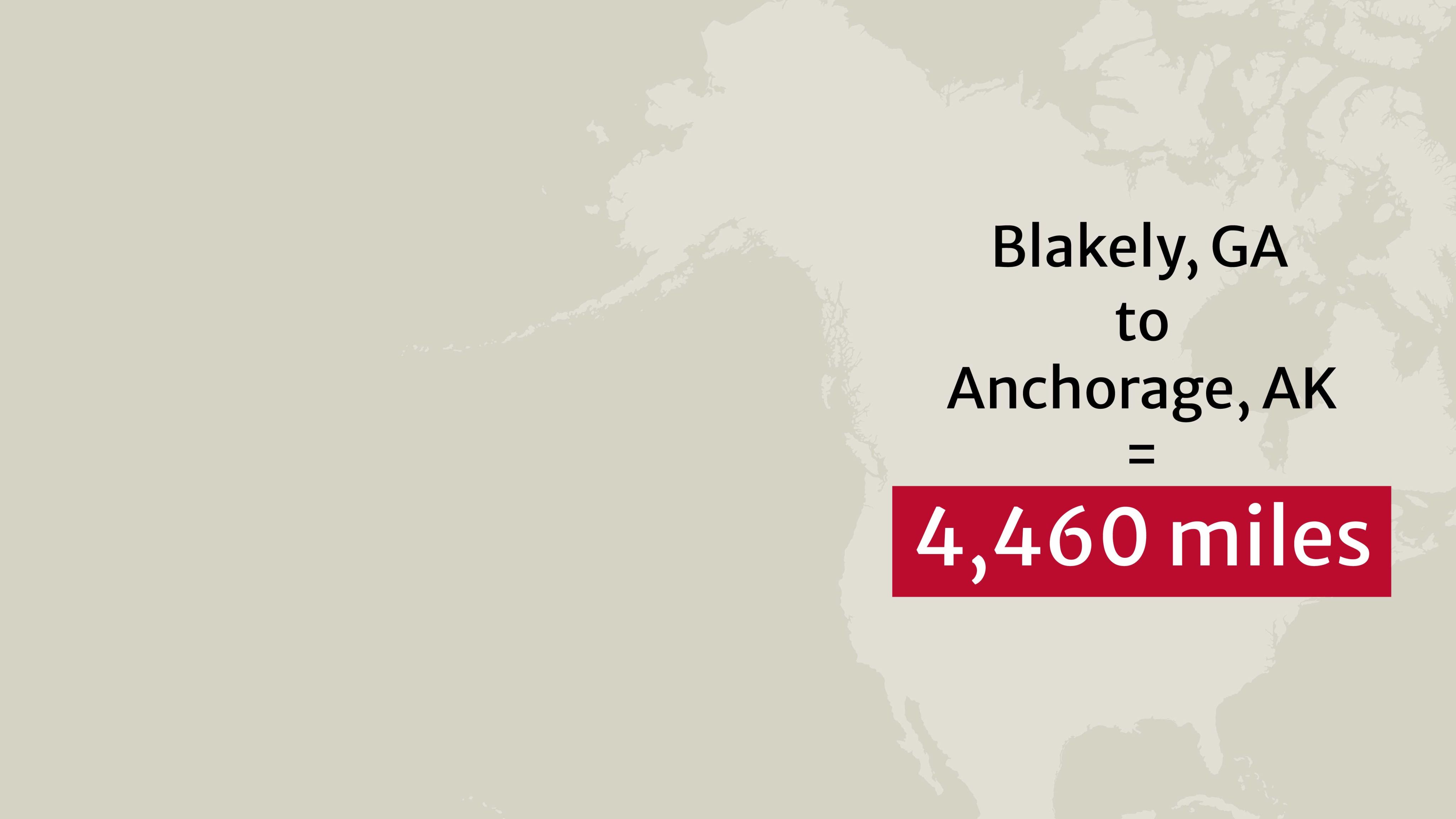

The city of Blakely in the Southwest corner of Georgia is about as far from the Alaskan backcountry as one can get in every way that counts – distance, climate, population. (Spoiler alert: Blakely is warmer and has more people. In fact, the population of Blakely – 5,371 as of 2021 – outnumbers its distance from Anchorage, Alaska, by 911 souls.)

For Blakely native Dr. Sonny King (DVM 1978), it was a pair of Jack London stories about dogs in the Alaskan Wilderness that fostered his affinity for dogs – The Call of the Wild about a prospector and his sled dog team chasing fortune in the 1890s Alaskan Gold Rush, and White Fang about a wild dog’s path to domestication in the Yukon Territory.

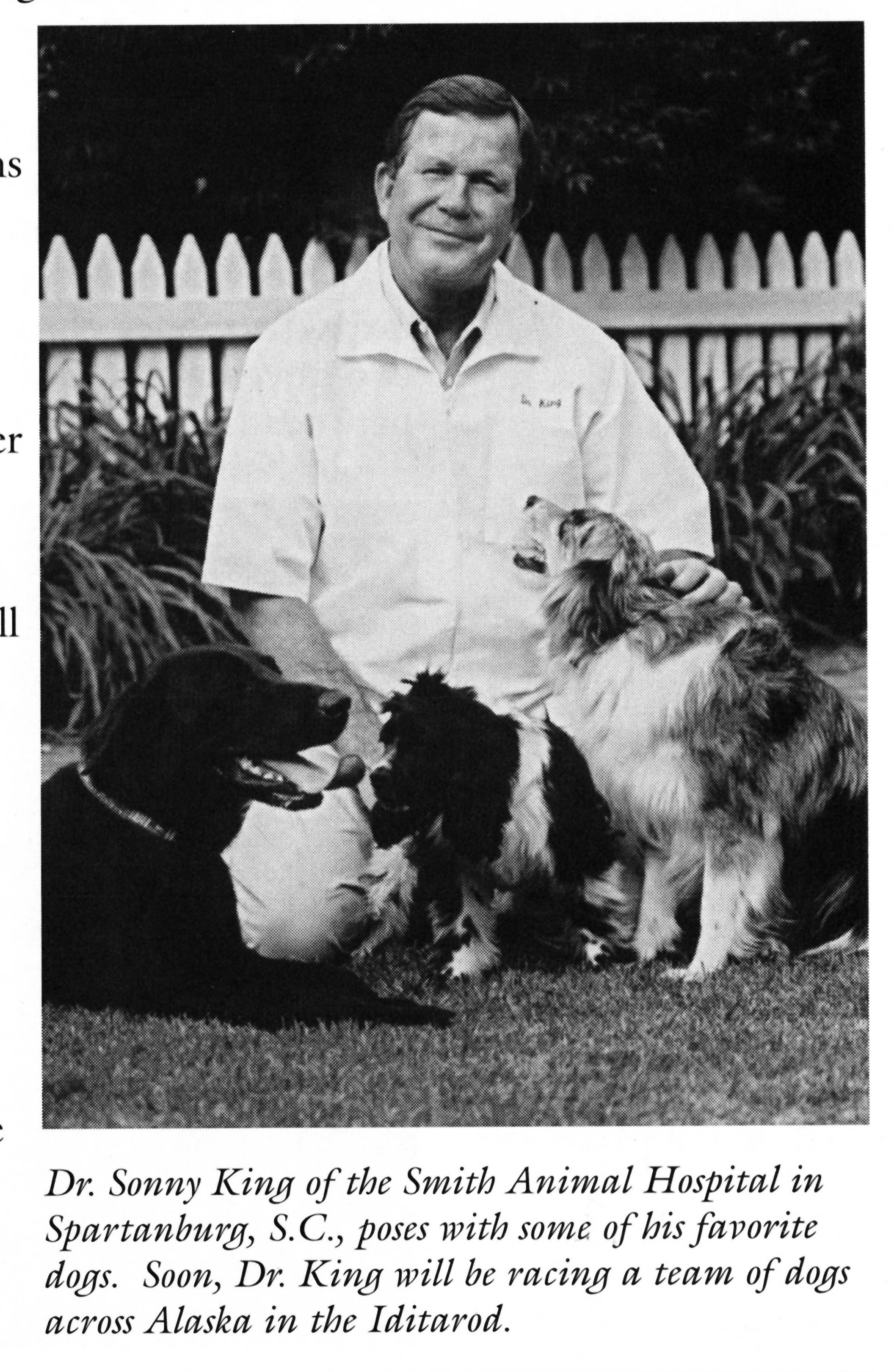

As a boy, King’s dogs were his companions as he roamed the woods of Southwest Georgia seeking London-esque adventures. As an adult nearing his 50th birthday and the owner of a small animal veterinary practice in Spartanburg, S.C., King heard the call of the wild again while following news coverage of The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, or The Iditarod as it is commonly known.

King volunteered to be a veterinarian on the race trail for the 1993 running of The Iditarod, and served again in 1994, 1995 and 1996. While caring for dogs on the trail King often asked the mushers what it was like racing between checkpoints. They told him he had to experience it first-hand to truly understand. So, in 1997 King hopped aboard a sled and ran a leased team of dogs. He came in 42nd in a field of 44.

“You couldn’t be in charge of your own destiny unless you had your own dog team. If you were using somebody else’s dog team, you weren’t in charge of anything. You were just along for the ride,” King says.

In 1998, he ran his own team and finished 25th. He raced again in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001, when he finished 9th in a field of 57. He ran his final race in 2002, finishing 28th in a field of 55.

“Probably one of the reasons that I did not race after the sixth year is I came off the race with a fractured elbow that I fractured in the first 300 miles. I had a stress fracture in my foot and also a torn ligament in my knee. That being said, I was able to finish the race.”

He hasn’t been back since.

“I have my friends call me all the time. ‘Come back up and be a judge. Come up and be a veterinarian. Come up and do this, come up and do that,’” he says. “Let me tell you how it is; if you're an alcoholic, you don't want to hang out at the bar if you can't drink.”

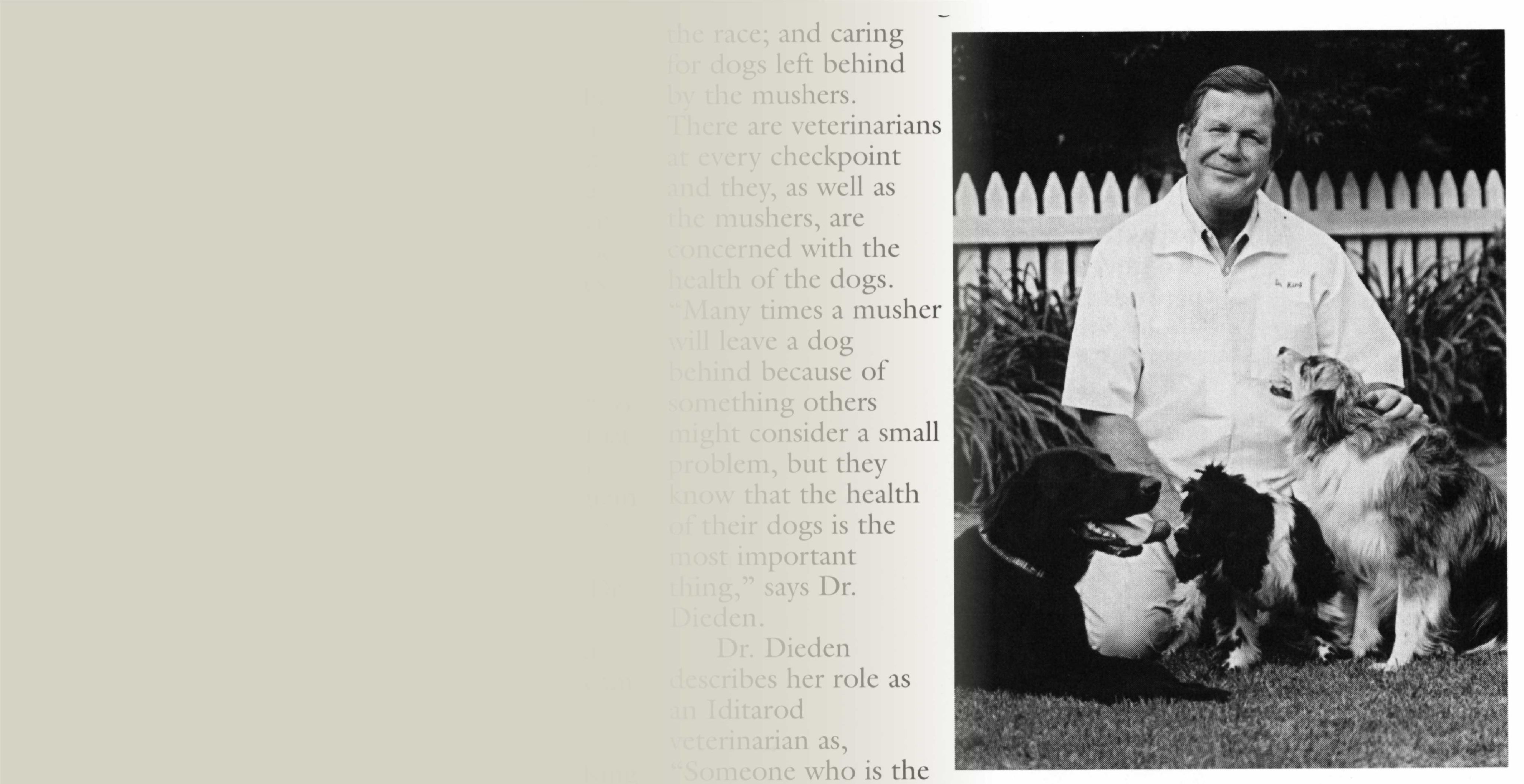

King's photo was featured in the Spring 1997 edition of the Aesculapian with his dogs in Spartanburg.

King's photo was featured in the Spring 1997 edition of the Aesculapian with his dogs in Spartanburg.

Sonny King (DVM 1978) segued from Iditarod veterinarian to musher. Al Townshend (DVM 1969) turned nutrition knowledge gained on the trail into a 30-year career consulting with pet food companies.

By Amy H. Carter

The city of Blakely in the Southwest corner of Georgia is about as far from the Alaskan backcountry as one can get in every way that counts – distance, climate, population. (Spoiler alert: Blakely is warmer and has more people. In fact, the population of Blakely – 5,371 as of 2021 – outnumbers its distance from Anchorage, Alaska, by 911 souls.)

For Blakely native Dr. Sonny King (DVM 1978), it was a pair of Jack London stories about dogs in the Alaskan Wilderness that fostered his affinity for dogs – The Call of the Wild about a prospector and his sled dog team chasing fortune in the 1890s Alaskan Gold Rush, and White Fang about a wild dog’s path to domestication in the Yukon Territory.

As a boy, King’s dogs were his companions as he roamed the woods of Southwest Georgia seeking London-esque adventures. As an adult nearing his 50th birthday and the owner of a small animal veterinary practice in Spartanburg, S.C., King heard the call of the wild again while following news coverage of The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, or The Iditarod as it is commonly known.

King volunteered to be a veterinarian on the race trail for the 1993 running of The Iditarod, and served again in 1994, 1995 and 1996. While caring for dogs on the trail King often asked the mushers what it was like racing between checkpoints. They told him he had to experience it first-hand to truly understand. So, in 1997 King hopped aboard a sled and ran a leased team of dogs. He came in 42nd in a field of 44.

“You couldn’t be in charge of your own destiny unless you had your own dog team. If you were using somebody else’s dog team, you weren’t in charge of anything. You were just along for the ride,” King says.

In 1998, he ran his own team and finished 25th. He raced again in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001, when he finished 9th in a field of 57. He ran his final race in 2002, finishing 28th in a field of 55.

“Probably one of the reasons that I did not race after the sixth year is I came off the race with a fractured elbow that I fractured in the first 300 miles. I had a stress fracture in my foot and also a torn ligament in my knee. That being said, I was able to finish the race.”

He hasn’t been back since.

“I have my friends call me all the time. ‘Come back up and be a judge. Come up and be a veterinarian. Come up and do this, come up and do that,’” he says. “Let me tell you how it is; if you're an alcoholic, you don't want to hang out at the bar if you can't drink.”

“You couldn’t be in charge of your own destiny unless you had your own dog team. If you were using somebody else’s dog team, you weren’t in charge of anything. You were just along for the ride."

Sonny King

The Ultimate Challenge

The Iditarod is a long-distance sled dog race that spans approximately 1,100 miles from Anchorage to Nome, crossing through harsh wilderness terrain, including frozen rivers and mountains. The race typically takes place in early March at the peak of Alaska’s winter. Mushers and their teams sometimes run in whiteout blizzard conditions, braving temperatures as low as -100 degrees F with wind chill.

King’s wife Mallie notes that men and women compete as equals on the Iditarod trail, but King says fellow mushers aren’t the toughest challenges a racer faces. “Your main foe is the great Alaskan wilderness and the awesome, brutal Alaskan weather.”

The 2025 race is being run by 33 mushers, the human drivers who control the sled pulled by a team of 12 to 16 northern breed dogs such as Alaskan huskies, Alaskan malamutes, and Siberian huskies. Mushing is a sport and a method of transport in frozen climates that dates back centuries.

The race is staffed by one paid veterinarian and about 20 volunteers who are assigned to more than 25 checkpoints along the trail where mushers stop to rest and feed their teams and seek medical care if necessary.

‘A Busman’s Holiday’

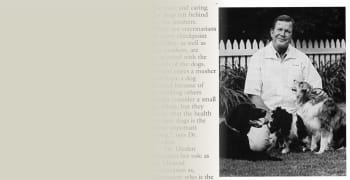

Dr. Al Townshend (DVM 1969) was already about two years into what would become a decades-long hobby when King arrived for his first Iditarod. “Being Georgia graduates, we just kind of bonded,” Townshend says.

More than just a way to live a real-life adventure story, volunteering as a veterinarian at the Iditarod was a way for Townshend to expand his professional knowledge, a sort of real-world continuing education opportunity.

“It was kind of a busman's holiday. You work on dogs all day long and take a vacation and go to Alaska and work on dogs under harsh conditions and all that,” Townshend says. “I really enjoyed it.”

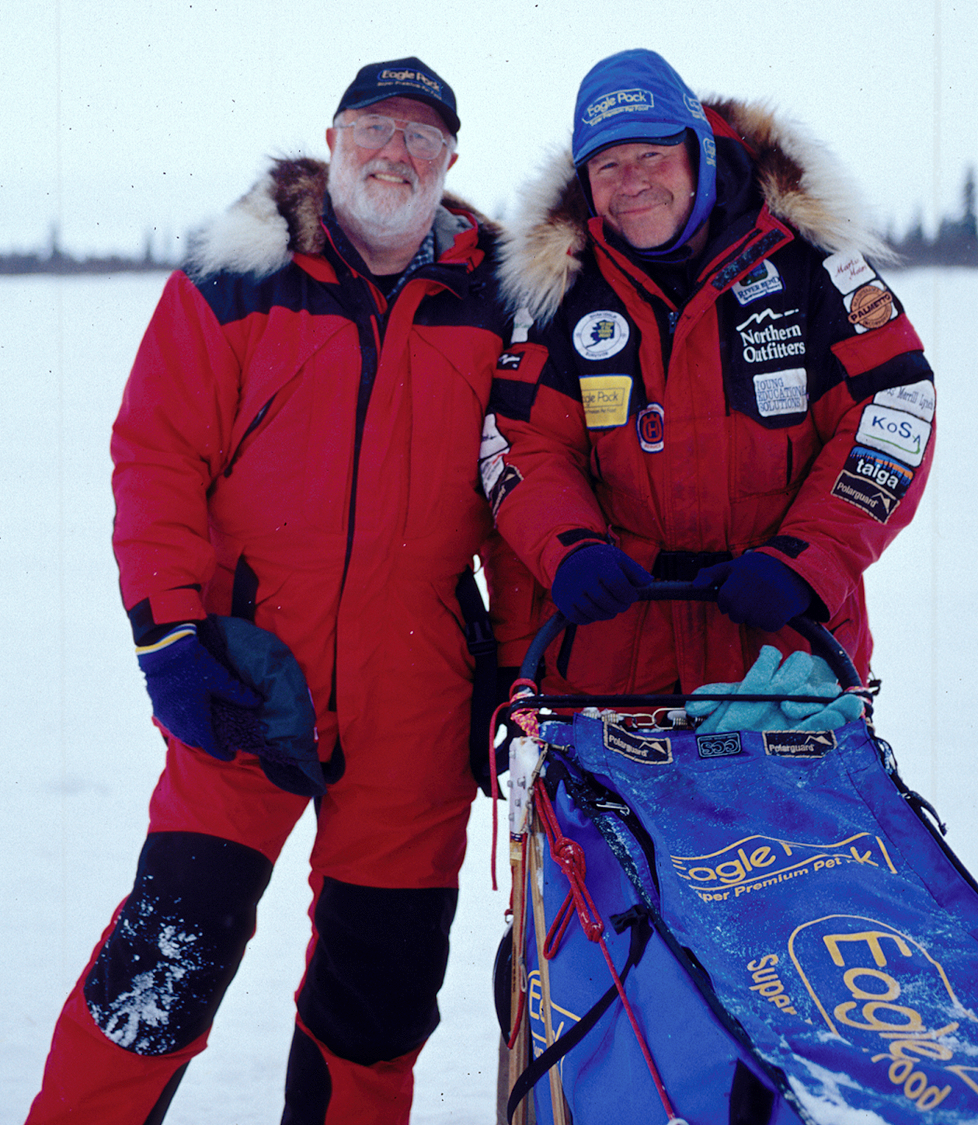

Townshend practiced in a very rural part of Maryland called the Eastern Shore where hunting is popular. He counted retrievers and pointing dogs among his patients – canine athletes like the ones that participate in the Iditarod.

“I was really into athletic dogs and these sled dogs just looked like they were amazing animals, and I wanted to not only go up and see as much as I could but learn as much as I could, too,” he says.

The race gave him new insights into diagnosing lameness in dogs by watching the way the dogs came into the checkpoints. “Most veterinarians, if the dog comes in limping, they examine it in an exam room and that’s about it. You know, you really need to get it outside and you really need to put it though its paces to really understand what is happening. I had to get much more detailed in my examination of a dog than I had in the past, too, you know, flexing the joints, abducting the joints, doing all those kinds of things and so I learned a heck of a lot that helped me in my practice when I came back.”

Three Hots and a Straw Bed

Volunteering at the race also made nutrition experts of King and Townshend.

“Sled dogs need anywhere from 10,000 to 12,000 calories a day. In human terms, for a 200-pound male that would be about 20 Big Macs a day,” Townshend says. The nutrition knowledge he gained from the Iditarod led Townshend to a job with a dog food company. He spent nearly 30 years consulting with pet food manufacturers to create nutritious food for dogs.

King fed his dogs at least three warm meals a day each day of the race. “You want that warm food in their belly and as soon as they do that they curl up on the straw you’ve got laid up and they sleep. So then when you get ready to get up and go you’ve got a highly nutritious snack, whether it be whitefish or it may be fat.”

If it’s cold – which in Alaska terms is subzero – the dogs need fatty snacks. If the temperature is zero or above, they need lots of water, which whitefish provides.

VetDawgs unite in Anchorage. (L to R: Townshend, King)

VetDawgs unite in Anchorage. (L to R: Townshend, King)

Townshend and a sled dog companion taking a moment to rest.

Townshend and a sled dog companion taking a moment to rest.

Townshend is pictured in Unalakleet, a remote village that serves as a checkpoint along the race route.

Townshend is pictured in Unalakleet, a remote village that serves as a checkpoint along the race route.

King pictured feeding his sled dogs one of their daily hot meals.

King pictured feeding his sled dogs one of their daily hot meals.

‘A Busman’s Holiday’

Dr. Al Townshend (DVM 1969) was already about two years into what would become a decades-long hobby when King arrived for his first Iditarod. “Being Georgia graduates, we just kind of bonded,” Townshend says.

More than just a way to live a real-life adventure story, volunteering as a veterinarian at the Iditarod was a way for Townshend to expand his professional knowledge, a sort of real-world continuing education opportunity.

“It was kind of a busman's holiday. You work on dogs all day long and take a vacation and go to Alaska and work on dogs under harsh conditions and all that,” Townshend says. “I really enjoyed it.”

Townshend practiced in a very rural part of Maryland called the Eastern Shore where hunting is popular. He counted retrievers and pointing dogs among his patients – canine athletes like the ones that participate in the Iditarod.

“I was really into athletic dogs and these sled dogs just looked like they were amazing animals, and I wanted to not only go up and see as much as I could but learn as much as I could, too,” he says.

The race gave him new insights into diagnosing lameness in dogs by watching the way the dogs came into the checkpoints. “Most veterinarians, if the dog comes in limping, they examine it in an exam room and that’s about it. You know, you really need to get it outside and you really need to put it though its paces to really understand what is happening. I had to get much more detailed in my examination of a dog than I had in the past, too, you know, flexing the joints, abducting the joints, doing all those kinds of things and so I learned a heck of a lot that helped me in my practice when I came back.”

Three Hots and a Straw Bed

Volunteering at the race also made nutrition experts of King and Townshend.

“Sled dogs need anywhere from 10,000 to 12,000 calories a day. In human terms, for a 200-pound male that would be about 20 Big Macs a day,” Townshend says. The nutrition knowledge he gained from the Iditarod led Townshend to a job with a dog food company. He spent nearly 30 years consulting with pet food manufacturers to create nutritious food for dogs.

King fed his dogs at least three warm meals a day each day of the race. “You want that warm food in their belly and as soon as they do that they curl up on the straw you’ve got laid up and they sleep. So then when you get ready to get up and go you’ve got a highly nutritious snack, whether it be whitefish or it may be fat.”

If it’s cold – which in Alaska terms is subzero – the dogs need fatty snacks. If the temperature is zero or above, they need lots of water, which whitefish provides.

Was he tired by the end? Yes. Lonely? No.

“I’ve got 16 dogs with me, 16 close friends that we’ve got about 2,000 miles in training prior to ever getting to the race. I’m not lonely. I’ve got a job to do constantly taking care of them because you don’t have any help. You have to do all this by yourself. It’s not like you’ve got a NASCAR pit crew to help you.”

Note: The 2025 running of The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race race began March 3 in Fairbanks, Alaska, about 360 miles north of Anchorage, the traditional starting point of the 1,100-mile racecourse. The change was due to the absence of snowfall along a 20-miles stretch of the usual course. The race is expected to conclude on Saturday, March 16, 2025.