A Woman's Work

Research and advocacy are hallmarks of the career that Doris Miller (DVM 1976) has forged at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

By Amy H. Carter

Dr. Doris Miller (DVM 1976) has experienced all that the University of Georgia has to offer from both sides of the lectern.

Miller serves as associate director of State Government Relations for the College of Veterinary Medicine and professor of anatomic pathology at the Athens Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

She did her undergraduate work at UGA, double majoring in poultry science and food science. She took advantage of a special program available at the time that allowed her to combine her final year of undergraduate study and her first year in the CVM.

“At that time your first year of vet school could count as your last year of undergraduate if you had gotten all the core courses,” she said. “So, in other words, your first year of vet school counted as your elective courses.”

After graduating with her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree, she spent a year practicing small animal medicine in Jacksonville, Fla. She returned to UGA in 1977 and enrolled in the graduate program at the Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Lab. At that time, students could do their first year of graduate studies in Tifton and transfer to Athens for the remainder of the program.

The Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Laboratory recently celebrated 80 years since its founding.

The Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Laboratory recently celebrated 80 years since its founding.

While private practice was her goal going into vet school, Miller experienced a shift in her thinking while working in Jacksonville. “I liked small animal practice a lot but there were so many unanswered questions. What is this tumor? Why didn’t this medicine work?”

She returned to UGA CVM to earn her master’s (1979) and Ph.D. (1981) in pathology, one of the few residency options offered at the time. She discovered an affinity for teaching undergraduates while in the program and joined the faculty after completing her Ph.D.

At this point, it had been nearly 30 years since the first woman graduated from UGA CVM, and Miller and her classmates were building upon that first woman’s trailblazing work. Between 1950 and 1972, the year Miller was accepted at CVM, the DVM classes at UGA counted no more than six female students among their number. Miller was one of 19 women in a class of 76 students.

“I wanted to do something professionally that was a service, an important service. And veterinary medicine is an important service.”

Just a smalltown girl

Miller grew up in Worth County about 200 miles southwest of Athens (35 miles northwest of Tifton) in a farming family. Her father also owned a meatpacking plant, where Miller gained familiarity with food animal medicine and food science.

As a youth, she discovered a passion for the plots woven by mystery author Agatha Christie, an important clue to remember as her story unfolds. In an interview during her junior year at CVM, Miller said she set her course for veterinary medicine in the seventh grade after reading a story about a mistreated puppy. “When you're 12 and a puppy is mistreated, it makes you want to cry,” she said at the time. “When you're 24, you want to do something that will prevent the puppy from being in pain.”

By that time, she also realized that veterinary medicine was more than just cute fuzzy puppies.

“As far as small animals go, pets are not just pets, they are the objects of real emotional attachment for many people. They are also used therapeutically in mental health,” she said in that 1974 interview. “And of course, it's easy for those of us who get our food at the supermarket to forget that a healthy livestock industry is essential. I guess you might just sum the whole thing up by saying, I wanted to do something professionally that was a service, an important service. And veterinary medicine is an important service.”

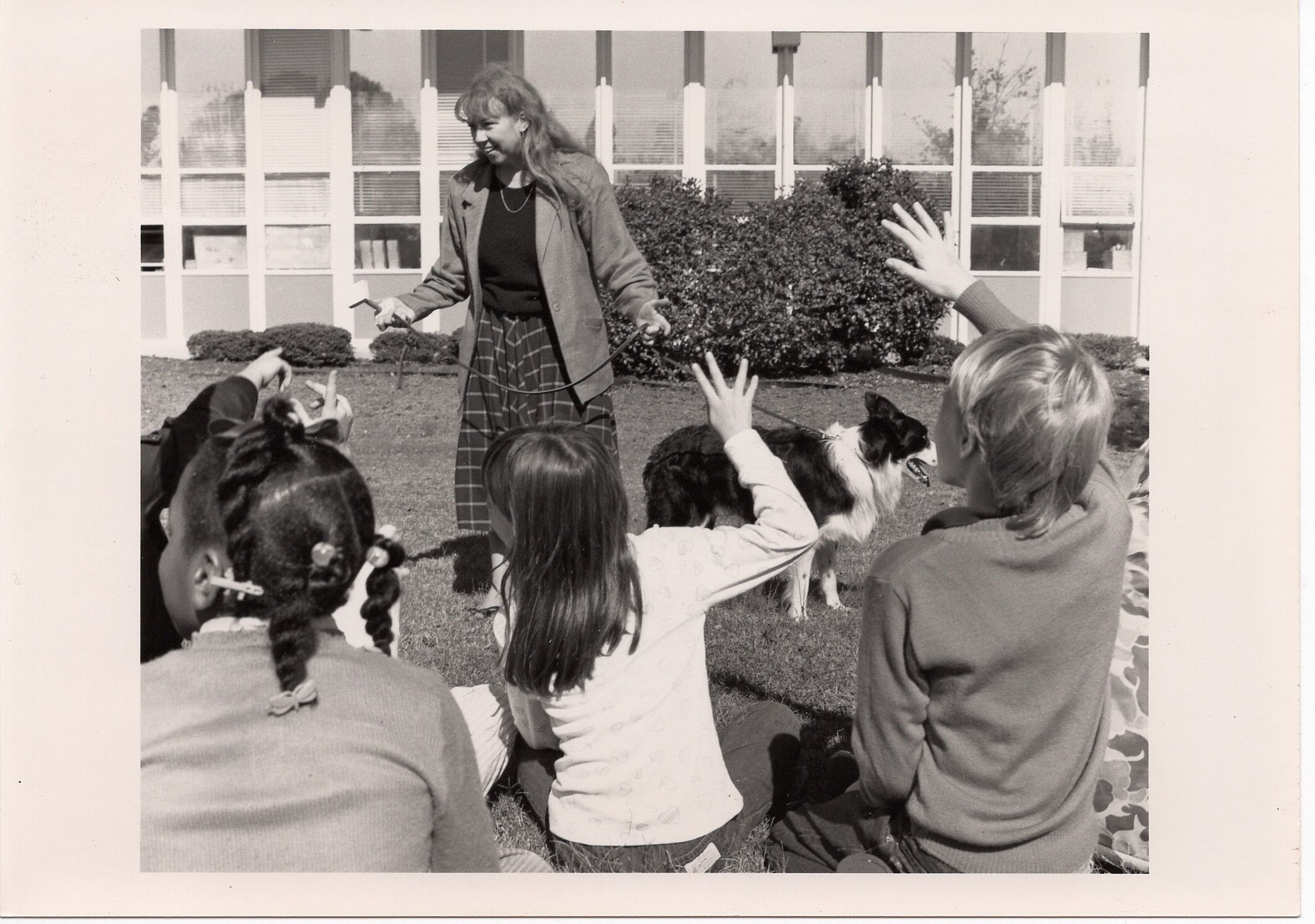

Miller sharing her passion for veterinary medicine with school children.

Miller sharing her passion for veterinary medicine with school children.

Who, what, when, where, why

Pathology is the foundation of vet med, providing answers to the questions that arise on the clinical and even legal sides, particularly at the Georgia Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Labs. There, samples submitted for testing sometimes raise questions that beg further research.

In 1978, the Tifton Lab identified what appeared to be feline panleukopenia virus in samples taken from dogs. “I remember when we first started seeing those cases,” Miller said. “We said, ‘But this is a dog. It's not supposed to have this disease.’”

The disease was later identified as canine parvovirus (parvo). It was a mutated version of the feline panleukopenia virus that jumped from cats to dogs.

Miller based her Ph.D. research on an outbreak of aflatoxin in corn in Tifton in 1977. At the same time, greater numbers of pigs than usual were testing positive for Salmonella. “They get Salmonella very easily anyway, but for some reason they were getting it more often. It was the corn.”

Miller tending to a porcine patient.

Miller tending to a porcine patient.

Miller focused on immune system suppression in the animals that made them more susceptible to Salmonella, eventually translating that research to fatty liver disease in humans.

And UGA’s Athens lab was among the first in the nation to diagnose and research melamine and cyanuric acid toxicity in cats and dogs that led to kidney failure. Melamine, a synthetic resin typically used as a low-pressure laminate for various products like furniture, cabinets, and dinnerware, was linked back to pet food in the 2007 outbreak of renal failure in small animals.

Around this same time, thousands of babies in China were also sickened by kidney stones caused by a melamine additive in their formula. When ingested, melamine causes the formation of insoluble crystals that cause kidney damage and failure.

Giving researchers the freedom to investigate such anomalies in the UGA labs was one reason Miller applied for the directorship of the lab. “I learned very quickly that if you don't have any say on where the money goes or you can't help raise the money, then it just ends right there. That was very frustrating.”

More than 50 years after she first embarked on her academic and professional careers with UGA, Miller is as engaged as ever, sharing her knowledge of forensic pathology with students and telling the story of UGA VetMed to professional organizations, state and federal legislators, and the public.

“I’ve enjoyed my career,” she said. “Hopefully I can stay around for a couple more years.”