Doctor, Senator, Governor, Chancellor

Dr. Sonny Perdue (DVM 1971) has built a life of public service on the foundation of his education in veterinary medicine. Now Chancellor of the University System of Georgia, Perdue advocates for higher education and the CVM.

By Amy H. Carter

Doctor, Senator, Governor, Chancellor

Dr. Sonny Perdue (DVM 1971) has built a life of public service on the foundation of his education in veterinary medicine. Now Chancellor of the University System of Georgia, Perdue advocates for higher education and the CVM.

By Amy H. Carter

In 2010 Dr. Sonny Perdue (DVM 1971), in his role as Georgia’s 81st Governor, initiated a $7.7 million appropriation from the state budget to the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine. The money kick-started planning for the construction of a state-of-the-art veterinary medicine learning facility, today’s teaching hospital.

Five years and more than $100 million from state and private sources later, the hospital opened to great fanfare on College Station Road. The 286,000 square foot facility sited on 150 acres replaced the older 50,000-square-foot hospital on main campus. The expansion has allowed the CVM to advance veterinary medicine by teaching and providing a host of specialties and services comparable to those offered by human medical facilities.

The UGA Veterinary Teaching Hospital recently celebrated 10 years at its new location on College Station Road.

The UGA Veterinary Teaching Hospital recently celebrated 10 years at its new location on College Station Road.

“It was good to be able to do that and great to see how that’s grown,” Perdue said, calling it one of his greatest memories of his two terms as Governor. Now 10 years on from the opening of the hospital, Perdue has served on the White House Cabinet as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and is currently serving as the chancellor of the University System of Georgia.

Since the first class of DVMs graduated from the college in 1950, alumni like Perdue have not only taken an outsized interest in shaping the future of the college as faculty and administrators, but they have also brought renown to the UGA CVM with their research, teaching and service.

From farm to clinic to voting booth

Perdue’s path to vet school started in Houston County on the diversified row crop farm and dairy he called home. “If you have a dairy you have to have veterinary services and there was an older veterinarian in town called Dr. Davis that would come out and care for our animals. He and I developed a friendship. He inspired me to become a veterinarian,” Perdue said.

As a ninth-grader in high school pondering future career opportunities, Perdue saw a profession that offered more financial stability than farming. “Farming back in that time, in the 1950s and ’60s, was fairly up and down as far as profitability, so I wanted a professional life.”

Farm work taught him focus and drive, but it didn’t afford him the opportunity to experience the day-to-day reality of a veterinarian’s work in an office setting. The first time Perdue did that was during his preceptorship between his junior and senior years of vet school.

Had he gotten that experience sooner or perhaps taken a personality profile test that measured his aptitude for the field, Perdue said he might have chosen a different profession, “but I’ll never regret my veterinary education here,” he said during a recent visit to the CVM on main campus.

Between his service in the U.S. Air Force and three years with a small animal clinic in Raleigh, N.C., Perdue was actively engaged in veterinary medicine for less than a decade after graduation. But his career in public service began while he was still in school.

“When I got admitted to veterinary school in the fall of ’67 Vietnam was really roiling,” Perdue said. “I had high school classmates that were drafted and sent to Vietnam and that was the last time I saw them. I developed an intense patriotic duty in that regard.”

He accepted an early commission to the Air Force that was offered to veterinarians, dentists, nurses and physicians at that time. Students commissioned through professional medical degree programs were permitted to remain in school until graduation if the military didn’t require their services sooner.

He went on active duty after graduating from the CVM in 1971 and was assigned to a public health mission addressing food safety for U.S. troops. Like so many medical advances born of war, food safety was a nascent field at the time and veterinarians who were well schooled in bacterial and viral infections were in demand to develop and enact protocols to prevent food-borne illnesses among military troops. Perdue was assigned to a base close to The Ohio State University, which also has a veterinary college.

“While most of our mission was food safety, we ran a clinic a couple days a week so I was able to use the skills that I learned in clinical practice there for the patrons of the base,” Perdue said.

After his discharge in 1974, Perdue went to work at Quail Corners Animal Hospital in Raleigh. Perdue worked in the clinic the summer between graduation and the start of his service in the Air Force, and persuaded a veterinarian he did his preceptorship with, Dr. Jim Jackson, to join Dr. Mike Bounds as a partner in the clinic. The three of them rotated schedules in a 24/7 operation at the Raleigh clinic. “There was no such thing as an emergency hospital at that point in time,” Perdue said.

It wasn’t long before he realized that the standard of care he was trained to perform and capable of delivering was above the means of many clients, and Perdue said he was bothered by obvious signs that some clients prioritized spending on their animals over their families.

Eventually, Perdue concluded that his temperament was not suited to an appointment-based practice. “I think had I done one of the psychological profiles or personality profiles early on I would probably have determined that an appointment system was not for me,” he said. Perdue said he found it difficult to focus on the client across the exam table knowing that he was falling behind on subsequent appointments with others.

“I never liked to keep people waiting,” he said.

Equally hard to ignore was the tug of home. Perdue liked Raleigh but missed Houston County and his family. “I never got over being homesick. Our extended family was in middle Georgia and while Raleigh was a beautiful place to live and a great community – we had great friends, a great church, great work family and everything – it just wasn't home at the end of the day.”

With wife Mary’s blessing, Perdue pondered a career change and returned to Georgia to start the first of three agribusinesses. He was appointed to a seat on the Houston County Planning and Zoning Board, which led to 11 years in the Georgia Senate and, in 2002, election to the first of two terms as Georgia’s 81st Governor.

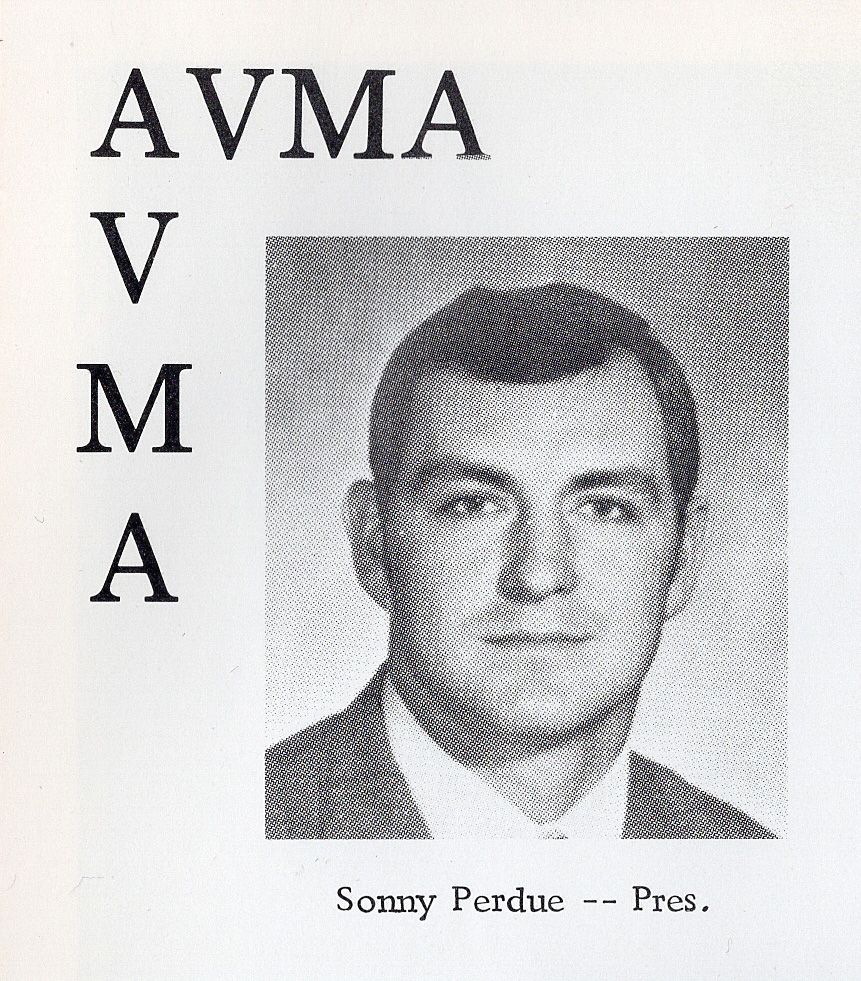

When he was a DVM student, Perdue was president of UGA CVM's student chapter of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

When he was a DVM student, Perdue was president of UGA CVM's student chapter of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

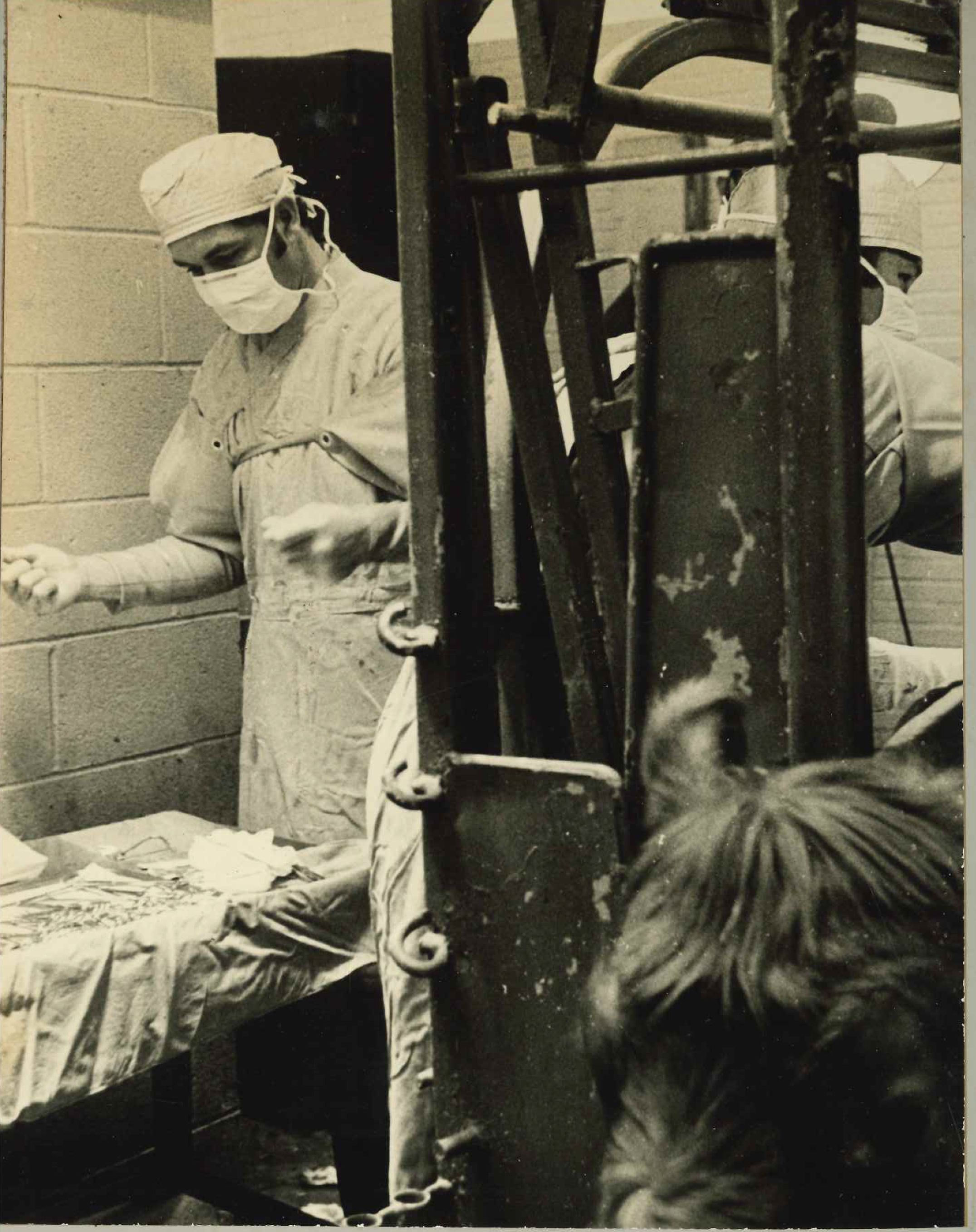

Perdue gowned, gloved, and masked for surgery

Perdue gowned, gloved, and masked for surgery

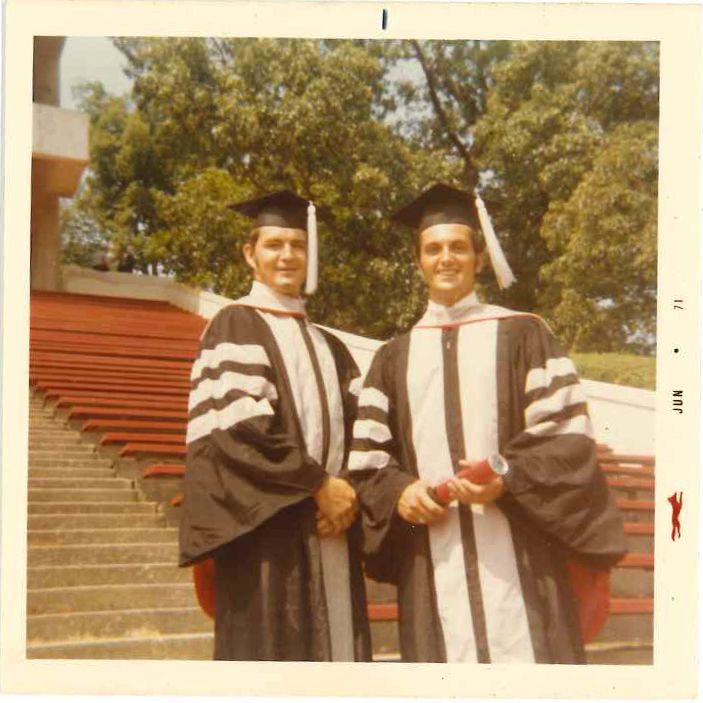

Perdue and his college roommate, Crispin Spencer, at graduation in 1971.

Perdue and his college roommate, Crispin Spencer, at graduation in 1971.

Back to school

Perdue was appointed the 14th Chancellor of the University System of Georgia in April of 2022, a role that entrusts him with oversight of the present and future of higher education statewide. And while his career as a practicing veterinarian was relatively brief, he still takes an active interest in the success of the CVM and the future of veterinary medicine in Georgia.

Chancellor Sonny Perdue gives his address during his Investiture Ceremony at the Georgia State Capitol. (Andrew Tucker/UGA)

Chancellor Sonny Perdue gives his address during his Investiture Ceremony at the Georgia State Capitol. (Andrew Tucker/UGA)

Issues like the dearth of large animal practitioners in rural Georgia are ones that concern Perdue in his current role. It’s a career path that requires long hours and low pay, making it a tough sell to students who’ve never been exposed to the field. “Veterinarians acknowledge that most large animal practitioners do that out of love not money,” he said.

Recruiting students from rural areas who want to return and serve their communities is key to reversing the loss of large animal practitioners, he said.

“I think to be successful in graduating large animal veterinarians we have to go get those kids who are raised in that kind of environment and have some degree of respect for that style of life and will go back into that range,” he said. “I think it's very difficult to take a young person, a young man or woman who's been raised in an urban environment and has had no large animal exposure, and try to persuade them that that's a great way to serve their profession and their clients.”

“I'll tell you that veterinary medicine taught me how to make differential decisions in life. . . .It's not just medical but that's the way good life choices are made as well, deciding day by day, moment by moment what's the right course of action to take.

Regardless of the path a student takes in vet school, the underlying education they receive will serve in every aspect of life, he said. It was his own education at the CVM that gave him the foundation for his life in public service. The systematic process that clinicians use to reach a diagnosis when multiple conditions are possible can be easily adapted to reach important decisions in life.

“I'll tell you that veterinary medicine taught me how to make differential decisions in life. You call them differential diagnoses but life is composed of choices and I still use the analogy for young people today that you've got to go from A to B to A to B to A to B down the decision tree eliminating the least preferable decision and go to the next and least preferable to get to the granularity and clarity of a good decision for life,” he said.

“It's not just medical but that's the way good life choices are made as well, deciding day by day, moment by moment what's the right course of action to take. I think the professional training that I learned at the College of Veterinary Medicine in Athens helped me to refine that in my life to make good life decisions.”