Ess-kuh-huh?

An origin story to explain, and enunciate, the insignia of veterinary medicine and the name of UGA CVM's Aesculapian magazine.

By Amy H. Carter

Ess-kuh huh?

An origin story to explain, and enunciate, the insignia of veterinary medicine and the name of UGA CVM's Aesculapian magazine.

By Amy H. Carter

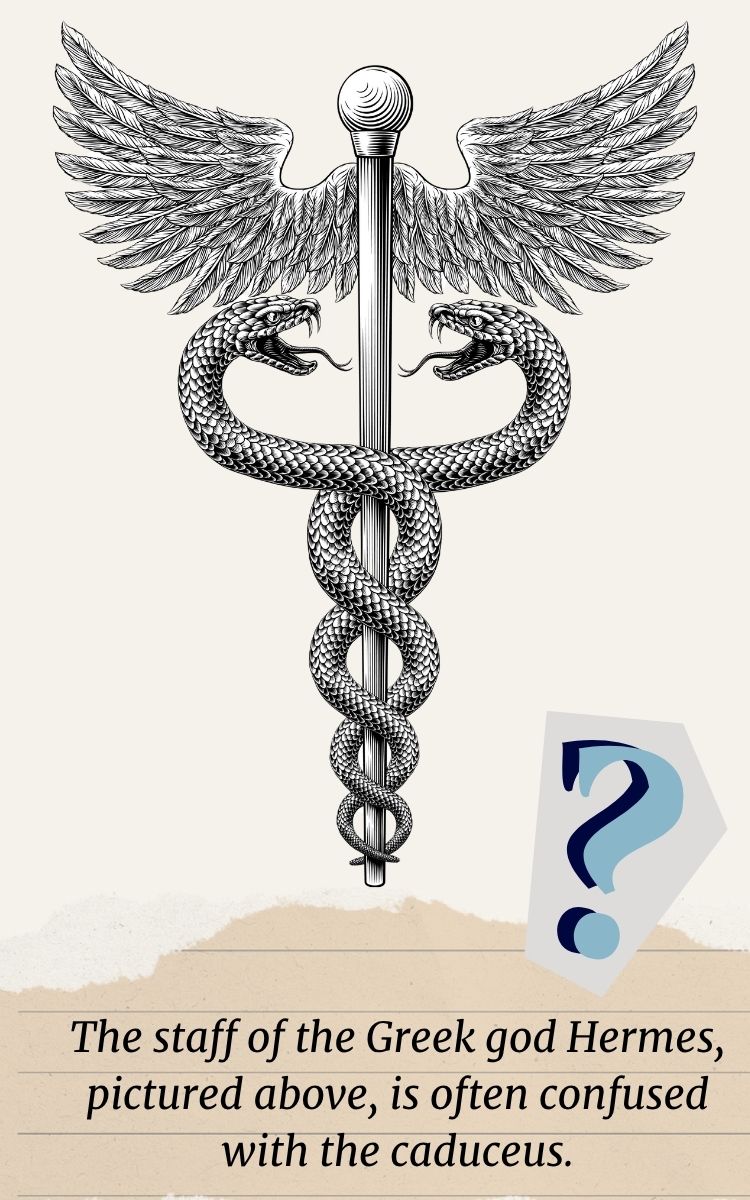

Just what is the Aesculapian, besides the name of the magazine of the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine? The Aesculapian (ess-kuh-LAY-pee-uhn) is the symbol used to represent the medical and veterinary medical professions. A rod entwined by a single serpent, the Aesculapian is often confused with the caduceus, the staff of the Greek god Hermes (Roman god Mercury), which is a winged scepter with twin serpents intertwined.

In the history of American veterinary medicine four different symbols, all linked to Greek and Roman mythology, have been used: a centaur, a winged horse’s hoof, the caduceus, and the Aesculapian.

The story of the Aesculapian begins in ancient Greece. Homer described Paeon (or Paean) as the physician to Olympus in his epic poem the Iliad. Paeon was superseded by Chiron, the legendary centaur who had the body and legs of a horse and the torso, arms and head of a man. Chiron was considered a master of music, astronomy, prophecy, botany and healing (using medicinal plants). He raised Asklepios, the son of Apollo (Greek god of speech, poetry and song), teaching him the art of healing.

Asklepios became a famous demi-god and healer around whom a cult developed. Eventually Asklepions or cult temples were established, and sick people were brought to them to be cured. Some of these temples became health spas and sanatoriums while others evolved into medical schools.

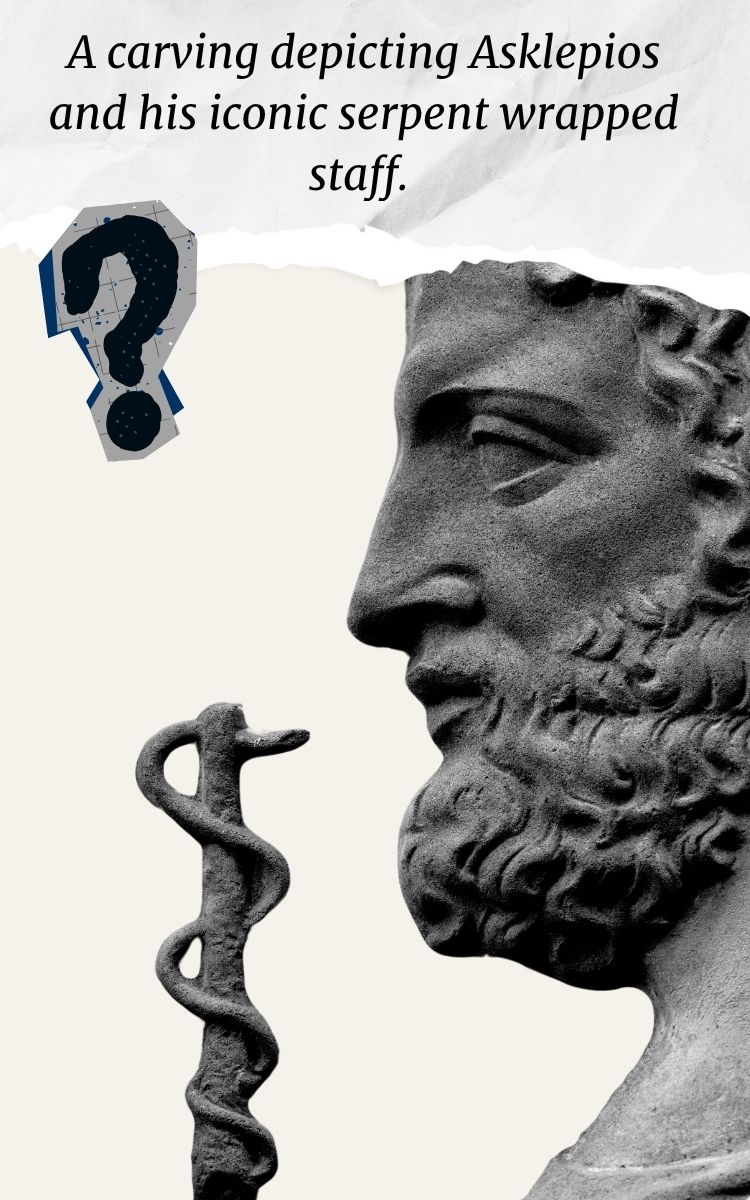

Snakes, which were common around the temples, became associated with the art of healing through the belief that they aided in cures through contact with sleeping patients, and Asklepios came to be depicted holding a staff with a single snake entwined around it. His snake-wreathed staff, which is now associated with medicine, is called the Aesculapian staff.

Similarly, the Greek god Hermes was depicted with a wand called a caduceus. Hermes’s caduceus was different from the Aesculapian staff because it was a winged staff with two snakes entwined around it. The wings on Hermes’s staff represented the wings on his sandals and petasos (traveler’s hat).

Even though Hermes had virtually no connection with medicine, his caduceus was adopted as a symbol of medicine by medical and veterinary organizations in the United States. Perhaps knowledge of the difference between the serpentine symbols died away, or maybe the caduceus became the favored symbol after American medical publishers, especially in the second half of the 19th century, began using a caduceus as their printers’ mark.

The practice continued with famous English physicians including Sir William Butts, who became surgeon to King Henry VIII in 1533, and Dr. William Harvey, the first to discover the circulatory system in 1649.

In modern times, the caduceus appeared on the chevrons of U.S. Army hospital stewards and later on the seal of the U.S. Public Health Service. In 1902 the United States Army Medical Department adopted it as its insignia. For a time the caduceus was also used by the American Medical Association. It was replaced with the Aesculapian staff in 1912.

In 1863 the United States Veterinary Medical Association (predecessor of the American Veterinary Medical Association) adopted the centaur, symbol of Chiron, as its seal. With the reorganization of the Army in 1901, veterinarians of the calvary and horse artillery were given a winged horse’s hoof to wear as their insignia. The wings represented those of the mythological winged horse, Pegasus.

When the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps was established in 1916, the caduceus was superimposed with the letter “V” and adopted as the corps’ official insignia. In 1921, the AVMA adopted the caduceus with a superimposed “V” as its emblem. Committees were convened in subsequent years to debate the appropriateness of this symbol, and in 1970 the AVMA adopted a resolution to discontinue use of the caduceus and replace it with an Aesculapian symbol superimposed with a “V.”

UGA VetMed’s alumni magazine has been called the Aesculapian for at least 52 years. The oldest issue on file at the college dates to 1973.

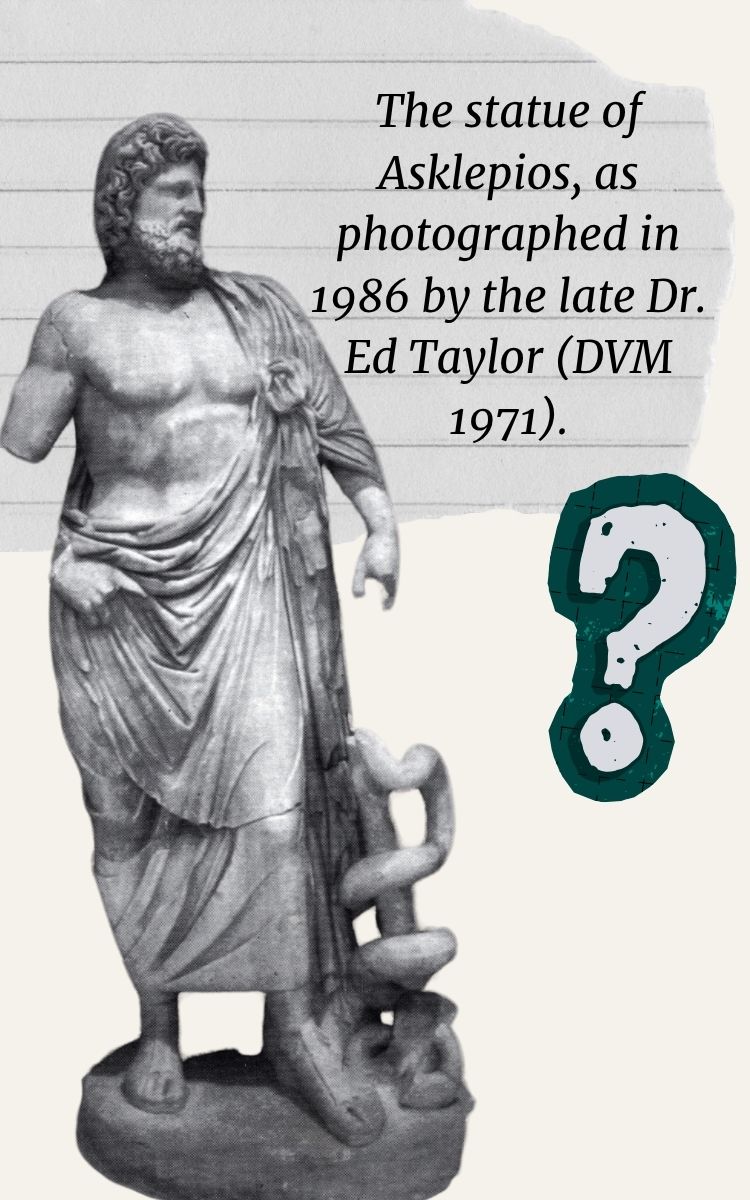

The cover of the Summer 1998 issue of The Aesculapian featured a photo of the statue of Asklepios taken in Athens, Greece, by the late Dr. Ed Taylor (DVM 1971), past president of the Georgia Veterinary Medical Association. Taylor wrote this about the trip and his chance encounter with Asklepios:

“I visited Greece to run the Athens Marathon in 1996 for a number of reasons. First, the 100th anniversary of the Olympic Games was being held in Atlanta and the 100th running of the marathon as a sporting event event was being held in Greece. The run followed the original course taken by Phidippides as he ran with the news of the Greek victory against the invading Persians from the plains of Marathon, Greece over the peninsula to Athens on the opposite coast. Since the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, the finish of the marathon is in the stadium built for the 1896 Olympic Games. It is difficult to describe the emotions of running 25 miles and then turning off the street to finish the run on the track of such a beautiful and historic stadium. Also, the date of the run was within two weeks of my 50th birthday and the coincidence seemed a perfect way to celebrate a healthy 50 years. After deciding to do the run, it was natural to turn my attention to the antiquities, and I really wanted to visit and photograph the Sanctuary of Asklepios. I was not able to visit Epidaurus, but I did sit in the Temple of Asklepios adjacent to the Parthenon and the Acropolis of Athens. The statue of Asklepios, which I photographed in The National Archeological Museum in Athens, was taken from the main sanctuary at Epidaurus. I found the statue quite by chance and was thrilled to get a photograph of our professional heritage. Asklepios is depicted as a bearded man leaning on an augur’s wand with a magic serpent. The ancient Greeks revered anything that came from the earth, and serpents were particularly admired and not viewed as evil or mystical.”

-Adapted from Origins of the Aesculapian in Veterinary Medicine, an article written by Linda Medleau (Editor) and Jeni Hatcher for the Summer 1998 issue of The Aesculapian, which has been the name of UGA VetMed’s magazine since at least 1973.